Can you believe we’re rapidly approaching the end of this series (Design for the Supply Chain) already!?! This week we’re talking about the meticulousness of the supply chain management solution.

Principle #8: Good design “Is thorough down to the last detail”

“Nothing must be arbitrary or left to chance. Care and accuracy in the design process show respect towards the consumer.” – ‘Dieter Rams: ten principles for good design’ My first reaction to this was to say something about Apple and Steve Jobs (A Story About Steve Jobs And Attention To Detail), but I figured you’ve probably already heard those stories before. So I started reflecting instead on how best to pay attention to detail.

“Nothing left to chance” means to me there’s a clear checklist of things that are carefully considered when establishing (or refining) the supply chain. This checklist would ensure the attention to detail goes beyond the vision of a single individual, or even trusting in corporate culture—both inevitably change over time. It would be systemic, a part of the structure of the company, and wouldn’t change without a conscience decision and a serious amount of thought.

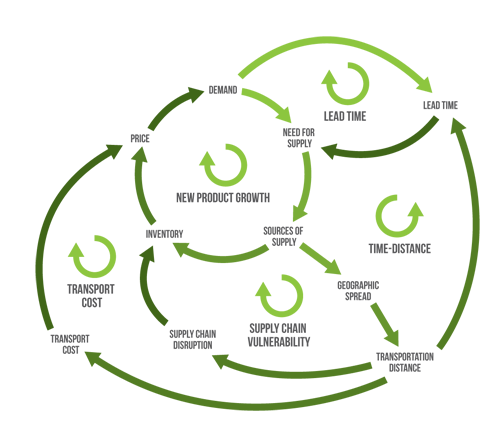

It brings to mind the concept of Systems Thinking, and one of my favorite tools: the causal diagram. I like it because it explicitly shows what's driving results, including any unintended consequences. It’s very hard to understand something as intricate as a supply chain without drawing a picture. I believe one of our challenges is how fatiguing it can be to give deep thought to the supply chain because it is so complex.

I was recently reminded just how complex a supply chain can be for a product as ‘simple’ as a pencil. I was listening to a Freakonomics Radio podcast (How Can This Possibly Be True?) that included a discussion about the essay, I, Pencil, which is written in the words of a pencil itself (check it out, it’s pretty cool!). The pencil talks about the processes and participants in its supply chain and how, “not a single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me.” Some points mentioned:

- The people who are involved in cutting down and machining the trees

- The people who designed the chainsaws and the axes and the trucks that ship the cedar across country

- Milling and cutting the wood into pencil-like shapes

- Workers who built the hydroelectric dam that powers the mill

- The lead, which is of course not made of lead but is graphite mixed with other stuff

- The graphite miners

- The men who built the ships that transport the graphite

- The harbor pilots who guide those ships in from the sea

- The lighthouse keepers along the way

- The lacquer on the pencil

- The brass on the top of the pencil (made from zinc and copper… which have to be mined)

- And the list goes on and on!

“The pencil explains all this detail, but in each case, the pencil is pointing out that there are these global supply chains, there are all of these different inventions going way back in history, all of these different people involved. And if you put it all together, you realize there isn’t a single person in the world who would really understand how to make a pencil from scratch, from the raw materials.” – Tim Harford, economist, journalist, broadcaster and author of The Undercover Economist.

The image above is a simple supply chain causal diagram from the APICS article, The Origins of Complexity. I can see integrating the elements of the company’s mission statement (e.g. sustainability), aspects of risk management (e.g. natural threats), etc. into this type of diagram. This view of the supply chain as a checkpoint could be very useful to help drive “thoroughness” in the solution. Are there other approaches or tools you would recommend to drive meticulousness in the supply chain?

Want to learn more about Design for the Supply Chain? Check out the rest of the series:

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 1: Industry 4.0

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 2: Innovative

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 3: Useful

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 4: Aesthetic

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 5: Understandable

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 6: Unobtrusive

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 7: Honest

- Design for the Supply Chain Pt 8: Long-Lasting

Leave a Reply