I have been in supply chain management longer than I care to remember, but there are others who have been in the field even longer, and their experience and wisdom is often on display. I follow the writings and opinions of George Palmatier because he is one of those that gives regular insightful comment. George has a thought-of-the-day email blast that I nearly always think about first thing in the morning, if I am not on the road and have time to digest. Last week one came through, and it was a beauty.

George’s statement that

I find many companies do planning, but then fail to monitor, manage and control the business once the planning is “done”.

I couldn’t agree more with George, to the extent that we have been using the terminology Plan-Monitor-Respond for over 2 years now. These are 3 different competencies, and all too often we focus only on the Plan portion in Operations. Actually this is true in general business too, but let’s keep it to Operations for now. There are reams written on how to create the perfect plan with many Masters and Phds awarded for research on generating an optimized plan, but very little is written about what happens once the plan is created, optimized or not. This is all good stuff and I was one of those graduate students pursuing the perfect plan many years ago. Much of this research and attempts to realize the result in the field have led to enormous strides in our understanding of Supply Chain. But I have moved on. George makes the statement that companies need to

“control the business as it responds to change – changes in market, customers, external influencers, and the competition, etc.”

This is a great statement, but it doesn’t go far enough, and here is why. George’s statement is based upon the assumption that the plan was correct, or, even worse, optimal, in the first place. It wasn’t. It was, and it should be, the best we could come up with at the time based upon what we knew about the market, but we had to make many assumptions about pricing, demand, supply, capacity and a whole host of other factors including exchange rates, fuel prices, etc. And guess what, a whole lot of those assumptions did not pan out. The point I am trying to make is that it isn’t changes in market, customers, external influencers, and the competition, etc. that is causing us to respond. What is causing the mismatch between what we thought would happen – the plan – and reality is that the plan was wrong in the first place. Nothing exemplifies this better than the fact that a recent study by Terra Technology shows that a forecast is typically no more than 52% accurate. 52%! And that represents a 6% improvement over an 8 year period. The average forecast accuracy for new products is 35%. One of the primary uses of the demand plan is to drive the supply plan. Well, if the demand plan is typically only 52% accurate, how accurate will be the supply plan? Can the supply plan ever be optimal given the forecast error? Of course the forecast error is not the only factor that will impact the quality of the supply plan since many assumptions have to be made about capacity and supply availability. Terra Technology and other vendors focused on demand have helped companies make tremendous strides in improving forecast accuracy, but the result is that the forecast error is still around 30%. This is a big improvement from 48%, but it is still 30%.

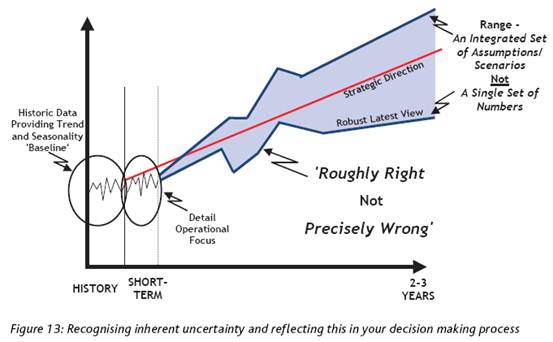

Of course this does not mean that planning is not important. Planning is very important, but planning, monitoring and responding must be equal and integrated competencies. In fact, responding to the mismatches between the plan and reality requires the creation of a new plan, but this needs to be done very quickly. So the key capability that is missing is monitoring – knowing that something is different and, more importantly, what impact this change has up and down the supply chain. But there is one more piece missing, namely know who is impacted – name, rank, and serial number – because only then can anyone take action to address the mismatch. But this brings up another issue with the current centralized planning systems, namely that planning is a team sport requiring collaboration, consensus, and compromise across several functions, often with competing objectives and performance measures. Reaching consensus can only be achieved through compromise based upon the evaluation and comparison of several scenarios simultaneously. In order to evaluate several scenarios you need a tool that will return results in seconds or minutes, not in 8 hours. Dick Ling and Andy Coldrick, while at StrataBridge, wrote a white paper titled “The Evolution of S&OP” in which they promoted the idea that the “One Number Plan” concept is flawed because of the inherent uncertainty in the plan. Instead a range of scenarios should be explored to test several assumptions in an integrated manner. In other words, scenario planning or what-if analysis should be performed from the very start because we do not have a crystal ball, that our plans are based upon many assumptions, some of which will be wrong.

The title of the graph captures the concept very well:

Recognizing inherent uncertainty and reflecting this in your decision making process.

In closing, it isn’t that planning is a waste of time, but rather that planning alone is not enough. To steal a term from Optimization Theory, planning is necessary, but not sufficient. You must be able to Plan-Monitor-Respond. These must be equal and integrated capabilities.

Discussions

One thing I have noticed over the years is that the life span of "The Plan" is getting shorter and shorter. Maybe a better term is "half life" because "The Plan" degrades exponentially rather than linearly. At some point, critical mass is reached where "The Plan" implodes/explodes and must be redone, hence the need to monitor and adjust, quickly.

Thanks for the comment. I'm presuming your "Good article" comment is a reference to the title of the blob? Namely that my opinion is good, but not God? ;-) Well, I would agree.

Yes, half-life is a good way to think of plan accuracy or risk.

But I can't state strongly enough that we all need to plan. What confuses me is the effort put into ensuring that the plan is achieved, even to the point of having plan conformance metrics, when it is the plan that is 'wrong'.

I want to be very careful here to distinguish between targets/goals and plans. Targets are aspirational and set the direction for an organization. Plans at one level are about how to achieve the goals, but these plans are strategic and more about which markets to enter, which technologies to pursue, etc. I am mostly refering to tactical plans as they relate to supply chains. What is our anticipated demand and how will we align the supply to satisfy the demand.

And of course we need always to understand the difference between something happening because we did not execute well versus because we did not have the right information (and therefoer the right plan) to start with.

Knowing that "The Plan" is inherently in error is not a reason to throw up our hands and not plan on either a strategic or tactical level. We need a guidepost or as I read in a previous post, a range of plans, to operate towards. And, not only do we need to plan, we need to measure performance against that plan and react to significant deviations in demand, supply, resources or time bucket. Not only that, we need to monitor and adjust the buffers in each (demand, supply, resources or time) and determine when they reach critical levels, either high or low while adjusting accordingly.

This is where most processes fail, even the one I am involved in on a daily basis.

My comment about the title was a joke, not meant seriously.

I agree with everything you write, especially the concepts of guideposts.

My only quibble, and its a quibble because the result is the same, is your use of the words "we need to measure performance against that plan". The reason I use different terminology is that this wording implies that the plan is the source of truth against which we need to measure our performance, and I am saying that the plan was never 100% correct anyway.

How I state it is that what we need to measure is when there is significant deviation of our plan from actuals, because after all the actuals are the "truth", we just assumed something different would happen. So we need to detect when our assumption are wrong and readjust.

It is a philisophical point but I think an important one. The one - measure performance against the plan - tries to make reality fit the plan, whereas the other - measure significant deviation of plan to actuals - is more about agility and responsiveness.

Leave a Reply